According to Tien Tzuo, CEO of Zuora and evangelist of his cause, the subscription model will spread to all sectors of the economy. His book Subscribed describes how companies adopt subscription packages one after the other. The list is impressive, from Netflix to General Electric, Salesforce, Adobe, Apple, General Motors, Schneider Electric, etc. From the most technological to the most basic, they all realize that the world is changing and that they must adapt. The two main reasons come from the transformations brought by the Internet, in particular the mobile Internet:

The Internet makes it possible to considerably reduce the friction associated with obtaining a service. Also, no more need to acquire, it becomes easier and more efficient to be served. Thus, we will no longer buy a tractor but make our fields plough, no longer buy a film but subscribe to Netflix, no longer buy a car but be driven by an Uber driver, no longer own our house but use Airbnb, etc. The object is multifunctional, but inefficient on each, the service can perfectly meet a unique function, so it is an improvement.

The Internet reverses the logic of competitive advantage: in the past, the latter was linked to the quality of a product that had to find its segmentation and marketing channels to reach the customer. Today, it depends on the relationship we can have with the customer, which allows us to calibrate an offer that is perfectly adapted to him. Interactivity allows this in-depth knowledge of the customer. Subscription is an essential part of the puzzle because it facilitates customer engagement, loyalty and therefore business stability. We no longer sell a product or service, we own the customer relationship.

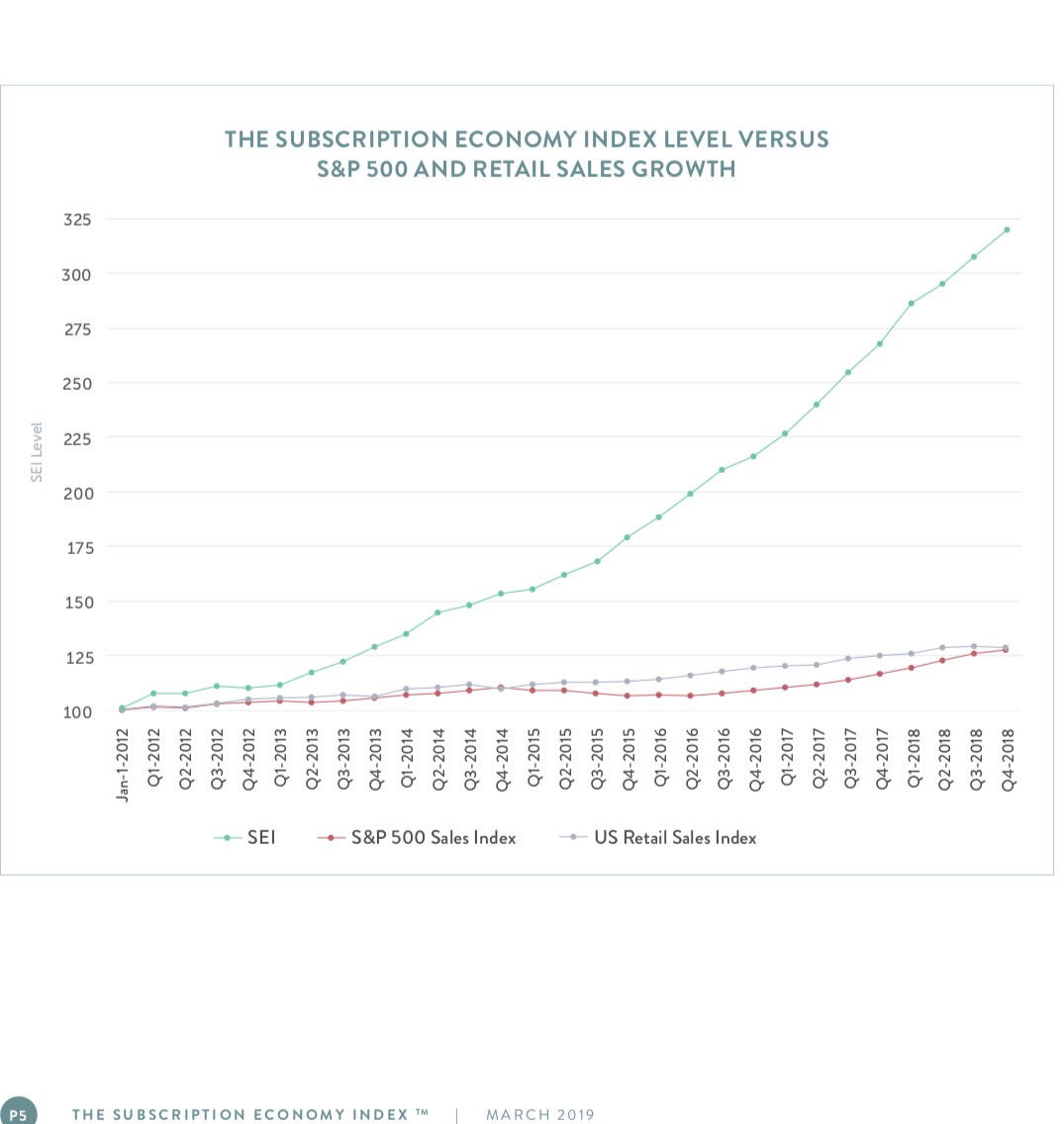

There are two main ideas here: with the Internet at your fingertips, 1/ leasing takes precedence over acquisition and 2/ subscription makes it possible to make this lease optimal for both the lessor and the lessee. So the subscription economy is intended to replace the traditional transactional economy. Zuora has designed a proprietary index that tracks the growth of the subscription economy (SEI or Subscriptions Economy Index). Its progress is impressive:

But what exactly is Zuora doing? It offers a software solution (in the form of a subscription, of course), which makes it possible to set up a high-performance subscription service (inventory management, invoices, reminders, payments, etc.). It is therefore in its best interest to promote this market and to distill the fear of missing the train. And it seems to be working: latest to date, Nike is launching a subscription package:

From TechCrunch:

Just in time for back-to-school shopping, Nike today officially announced its entry into the subscription service market with the launch of a “sneaker club” for kids called Nike Adventure Club. The new program is specifically designed to make shopping easier for parents who struggle to keep up with their quickly growing children’s shoe needs. Instead of taking kids to the store and trying on pair after pair to try to find something the child likes, the new Nike Adventure Club will instead ship anywhere from four pairs to a dozen pairs of shoes per year, depending on which subscription tier parents choose.

Isn't there some kind of bubble on the subscription model ? What is the real situation? To better understand, it is necessary here to introduce a simple law:

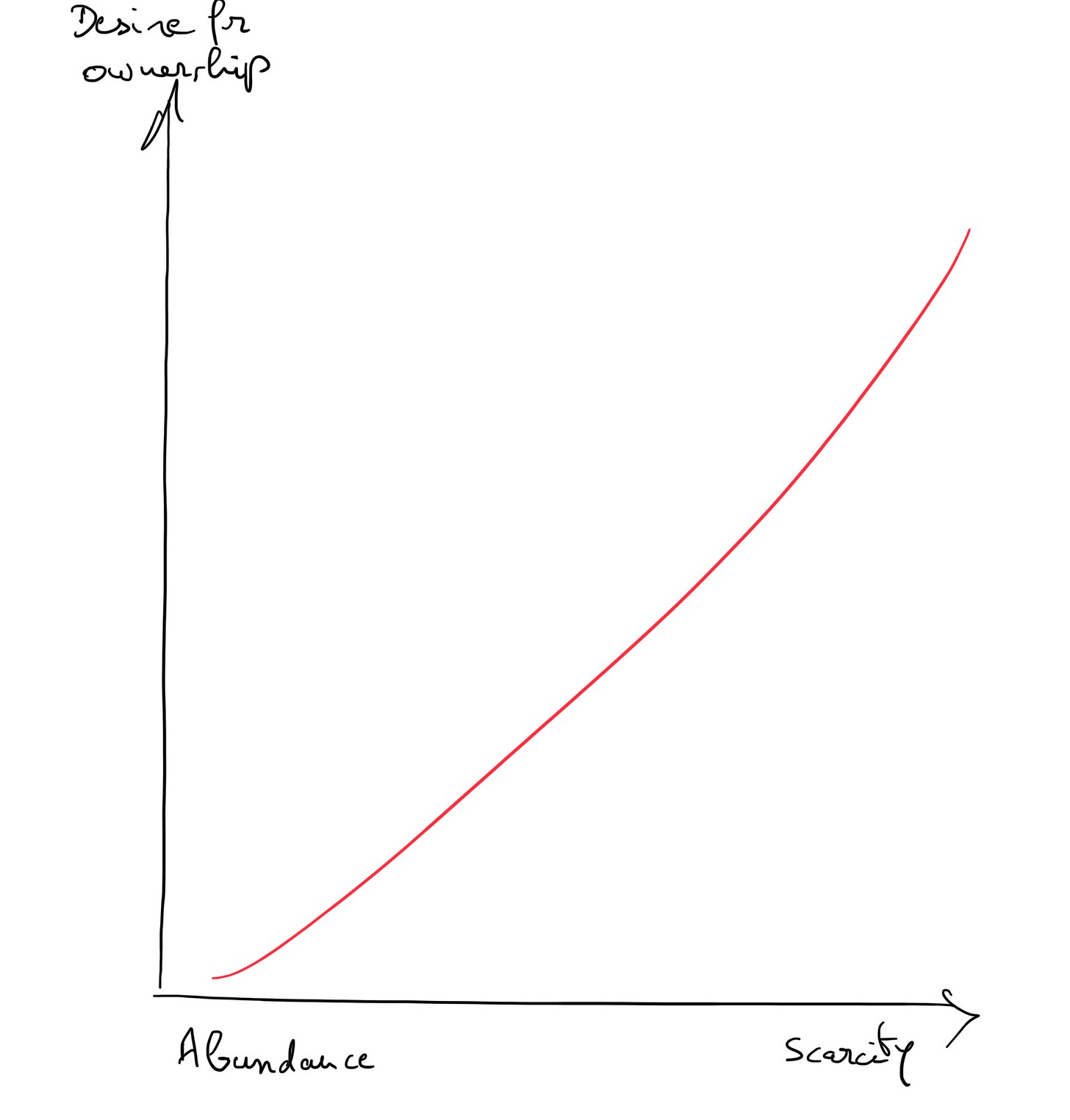

the more exclusive a property is, the more desired its possession is. And its corollary is also verified: the more substitutable a good is, the more indifferent one is to appropriate it.

Real estate is a striking illustration of this law: a real estate property is indeed unique, not by its construction but by its location. Each parcel of space is unique and therefore cannot be substituted for another identical one. However, it is easy to see that ownership of real estate is universally desired:

In feudal times, the excluded sought to gain land ownership rights, usually vested in kings and the church, and then to cement them by taking control of parliaments. Closer to home, after the Second World War, the rate of home ownership increased considerably. It can even be said that this desire to own one's home at all costs was a primary cause of the 2008 crisis, the "subprime" crisis. Contrary to what Tien Tzuo claims, it is unlikely that Airbnb will supplant the desire for access to private property. Governments have understood this and through electioneering are doing everything they can to facilitate access to home ownership.

On the other hand, digital assets are reproducible at will without any friction. Their possession is not desired. Typically when you buy a digital book from Amazon, you don't really know who it belongs to (Amazon can later make changes to that book), but to whom does it matter? The law of real estate ownership is much more clearly defined with the intervention of a notary, etc. Digital assets can very easily be used to the rental model and therefore subscriptions (Spotify, Netflix, Zoom, Slack, Dropbox, etc.)

The possession of an exclusive, rare property gives power and is a sign of that power. No one can encroach on this property or appropriate it. The ownership of an exclusive property distinguishes the individual from his or her peers. The will to power being intrinsic to man, it is not surprising to see this propensity to hold exclusivity. In contrast, what is common, abundant, is only valued for its utilitarian aspect, so it can very well be rented or borrowed.

The following graph shows the relationship between ownership propensity and exclusivity (scarcity):

The subscription therefore comes up against a first wall: the desire for ownership and it is not adapted to the customer's wishes in the case of exclusive goods or services: real estate, Ferrari, Apple, luxury goods, etc. Apple has 420 million paid subscribers to its digital services, but most of them are exclusive to IOS, reinforcing hardware exclusivity and its desire for ownership. Surprisingly (at least for Tien Tzuo, who praises Apple's "services" division in his book), sales of the "wearables, home and accessories" division are growing at a much faster rate than those of services (48% versus 16%) to reach $5.5B this quarter.

That being said, the Internet produces abundance at your fingertips, thus greatly facilitating indifference towards property. The object is considered only by its functional side and then reveals its imperfections. A car is used to transport passengers and goods. If you live in a large city, is it really necessary to have both functions, especially if you compare them with the disadvantages: difficulty of parking, cost, potential accidents, etc.? You might as well use Uber when you need to move and Amazon to move goods. However, between the service model provided by such companies as Uber, Airbnb, etc. and the subscription model, there is still a big step to take. Amazon was able to grow without Prime until 2005; this subscription formula represents only 7% of sales in 2018. Facebook does not offer a subscription and yet capitalizes $500 B. Tien Tzuo erases this difference in his book.

There is a specific insurance logic in the subscription model. Insurance means risk to be covered: through subscription, we pay now for a guaranteed service in the future. This idea is contradictory to the idea of abundance: if a good exists in abundance, why cover up against its disappearance? Such an analysis would lead us to affirme that the subscription business model is not adapted to either scarce or abundant goods.

In fact, the subscription is not used to cover the risk of shortage but the risk of the cost of abundance. Just as risk pooling makes it possible to reduce the cost of insurance by playing on the law of large numbers, so too does taste pooling make it possible to make the price of a subscription attractive. In insurance, we avoid extreme risks, in subscription we avoid extreme tastes: great successes (always scarce) can be better monetized otherwise because people are willing to pay more for them, flops are to be avoided as a waste. We end up with what is average but in real abundance at a reduced price. That's why Disney will unveil "Avengers" first in theatres, Netflix will focus on mean movies that are very adapted to the tastes of its subscribers, the "Kindle illimited" offer will not include the major bestsellers, etc. The bouquet lowers prices but is based on second choice. Thanks to taste-pooling , the price of a Spotify subscription is equivalent to the purchase of a single Taylor Swift album. iTunes theoretically offers abundance but the price is such that it is better to choose a more average subscription offer (Netflix, Prime Video, Hulu).

Finally, a subscription offer requires a subtle balance between supply and demand. Indeed, a company under the law examined above will be all the more likely to retain ownership of its production in order to exploit it as a rent, if its production is exclusive, scarce. Thus, IBM's first computers were rented, the customer had no choice, the land companies renting their property are more valued on the stock market than the developers selling them, etc. To succeed in a subscription offer, it is necessary to acquire the customer at the lowest cost, to encourage him to keep his subscription as long as possible and to achieve high gross margins. The subscription offer for an exclusive property meets all three conditions, but goes against the customer's desire for possession. The subscription offer for an abundant good does not meet any of the three conditions, but can be requested by the customer, if the pooling reduces the price. How to solve this paradox? There are two ways:

The rarest is that the good/service produced is scarce for its designer and substitutable for the customer. One example is the cloud. AWS's multiple servers are linked to a physical location and connected to each other by powerful cables. The coverage of the territory is important for the transmission speed, security and regulations to which customers are subject. A server farm includes between 50,000 and 80,000 servers on a surface area of 30,000 m2, all in 70 regions. AWS is above all a real estate portfolio, which presents a high degree of exclusivity, pushing the company to adopt the subscription business model. On the customer side, the ingredients are also gathered for the subscription: a computer is a commodity, in addition, the sharing of basic servers makes it possible to significantly reduce the cost of abundance. AWS does not need IBM's advanced servers, intelligence is in the network. So there is a perfect match between supply and demand.

Another possibility is to exchange exclusivity for exclusivity: the company by a subscription offer acquires the customer by a high-level service, taking advantage of the interactivity of the Internet, makes him a fan and receives a long-term rent. The customer, for his part, acquires an exclusive relationship with the subscription provider, based on the assurance of a differentiated service. The exchange of exclusivity is then the necessary condition for a successful subscription offer.

There is therefore no reason to believe that the subscription economy is eating the world. The conditions for success are limited and demanding. There will be many called (by Zuora among others) and few chosen...it would be more accurate to say that bubbles are eating the world.