Cemeteries are full of companies that didn’t understand the power game.

From the pinnacle to the abyss

Softbank and its Vision Fund have become the focus of attention for the technosphere in recent weeks: the fiasco of the WeWork IPO (valuation sinking from $47 billion to less than $20 billion in a few days) raises fears that the dark hours of the 2000s will return, i.e. the bursting of the technology bubble.

From WeWork, we quickly go back to Softbank, which becomes the scapegoat for the so-called bubble:

WeWork is more than 20% owned by Softbank and the Vision Fund. The Vision Fund injected $4.4 billion in 2017 on a $20 billion valuation and Softbank $2 billion in 2019 directly on a $47 billion valuation, as Vision Fund investors did not follow on such a valuation. In total SoftBank and its various entities have a $10.65 billion commitment on WeWork (source S1 WeWork)

It should be recalled that Softbank launched the Vision Fund in November 2016 with $25 billion of its own money and the balance coming from major investors such as the Saudi Arabian sovereign fund ($45 billion), the United Arab Emirates sovereign fund ($15 billion), Apple ($1 billion), Microsoft, Qualcomm, etc. The ambition of Masa Son, the founder of Softbank, is to raise a second fund (Vision Fund 2) of $100 billion. This time he's ready to put $38 billion out of SoftBank's pocket. It is therefore in his interest to increase the value of Vision Fund 1 to show that it is performing well and attract investors to the latter. This is the advantage when you do the valuations on your own !

This suspicion is reinforced by the history of Softbank's investment in Uber. In early 2018, the Vision Fund invested $7 billion in Uber (200 million shares at $32.87). These shares were purchased from the sulphurous CEO Travis Kalanick. In addition, Softbank invested $1 billion at $48.77 (which allows it to show that Uber is worth more than the initial $7 billion)... Uber's valuation miraculously rose to $82 billion for the IPO, allowing the Vision Fund to achieve excellent performance on paper. The company was finally introduced at $45 ($75 billion) and is now worth $33.

The third pillar of the "gonflette" thesis is Slack: the Vision Fund participated in a $250m funding round in 2017 on a global evaluation of $5.1 billion. In May 2019, Slack was valued at $16 billion in private valuation…it’s now a $13 billion company.

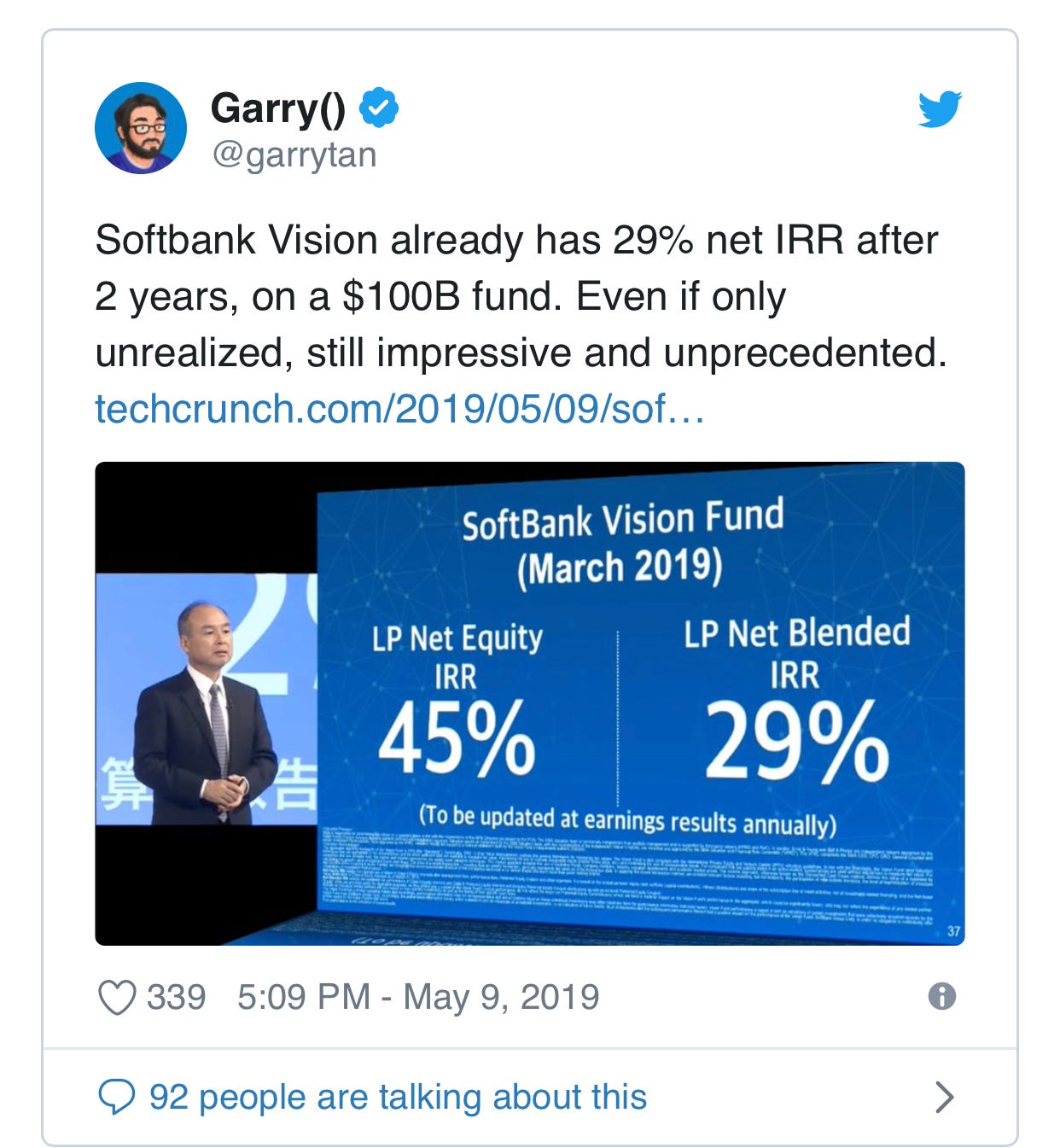

Everything would then contribute, in spring 2019, on the basis of private valuations to make Maya Son the visionary of the century:

Obviously a few months later, the situation changed: Uber missed its IPO and quickly tanked, SoftBank is at loss on its position. Slack was directly listed and after a very good start collapsed to $13 billion, below the May valuation. Finally, WeWork has waived its introduction, as the first anticipated quotations are too low. The press is raging on WeWork and goes up on SoftBank accused of profiteering of central banks helicopter money. Ben Thomson, a highly respected analyst in Silicon Valley, also scratches SoftBank, accusing it of confusing size and profitability:

That certainly paid off for Son with SoftBank’s Alibaba investment, which made SoftBank’s future forays even possible. Still, is “big” or “potential to be big” sufficient grounds for investment? Vision Fund’s portfolio is extremely heavy on “real world” companies in sectors like transportation and logistics and real estate, as well as fintech, another sector with significant capital needs. At what point does the search for “big” result not in investments with outsized potential but rather investments with outsized capital needs?

Ben Thomson strikes where it hurts: SoftBank invested $20 million in Alibaba in 2000. This $20 million became $140 billion (an annual return of 60%). This investment alone contributed more than 100% to SoftBank's performance. We can easily extrapolate, considering that other investments have destroyed relative value, that Masa Son pleases itself with large investments that make the headlines and flatter his ego. Masa Son thus becomes the symbol of the excesses of contemporary capitalism based on the mountain of liquidity offered by central banks.

In fact, Silicon Valley was extremely affected by the 2000 technology crash that caused a funding shortage for years. This crisis was caused by a period of undifferentiation during which companies and investors forgot the notion of competitive advantage and price to copy each other and invest on any business plan, provided it includes the suffix dit net or dotcom, at any price. Since then, Silicon Valley has learned the lesson and built on differentiation. The new bible is Peter Thiel's book From zero to one, which explains that the key to success is to be ten cubits ahead of the competition. Regularly, it is necessary to find a scapegoat who takes the blame for the lack of differentiation and allows the system to continue. This is how WeWork and SoftBank are the ideal culprits.

SoftBank's DNA

The reality is more complex regarding SoftBank. First of all, Masa Son is a clever and visionary businessman and investor. Born in 1957 in Japan, he went to Berkeley University to study engineering at university and then returned to Japan to found SoftBank in 1981. Masa Son then asked himself some essential questions before choosing his path. He had to find a business that met the following criteria:

to be passionate about it for the next 50 years

to offer a unique product, which others do not do

to be number 1 within 10 years, in Japan

in a sector that is likely to grow in the next 30 to 50 years.

The computer seemed to be a promising way to go at the time. Masa Son then refined his search. For him, the computer could be compared to the human head: there was the skull (the computer itself,), the brain (semiconductors), wisdom (software) and finally knowledge (data). For him, the most interesting were knowledge and wisdom: he chose wisdom, i.e. software, then knowledge. We can then bow to such a premonitory vision. From Marc Andreessen's famous phrase proclaimed in 2011: "software is eating the world" to the artificial intelligence that seizes the entire economy, we must not forget that Masa Son at 24 saw this future.

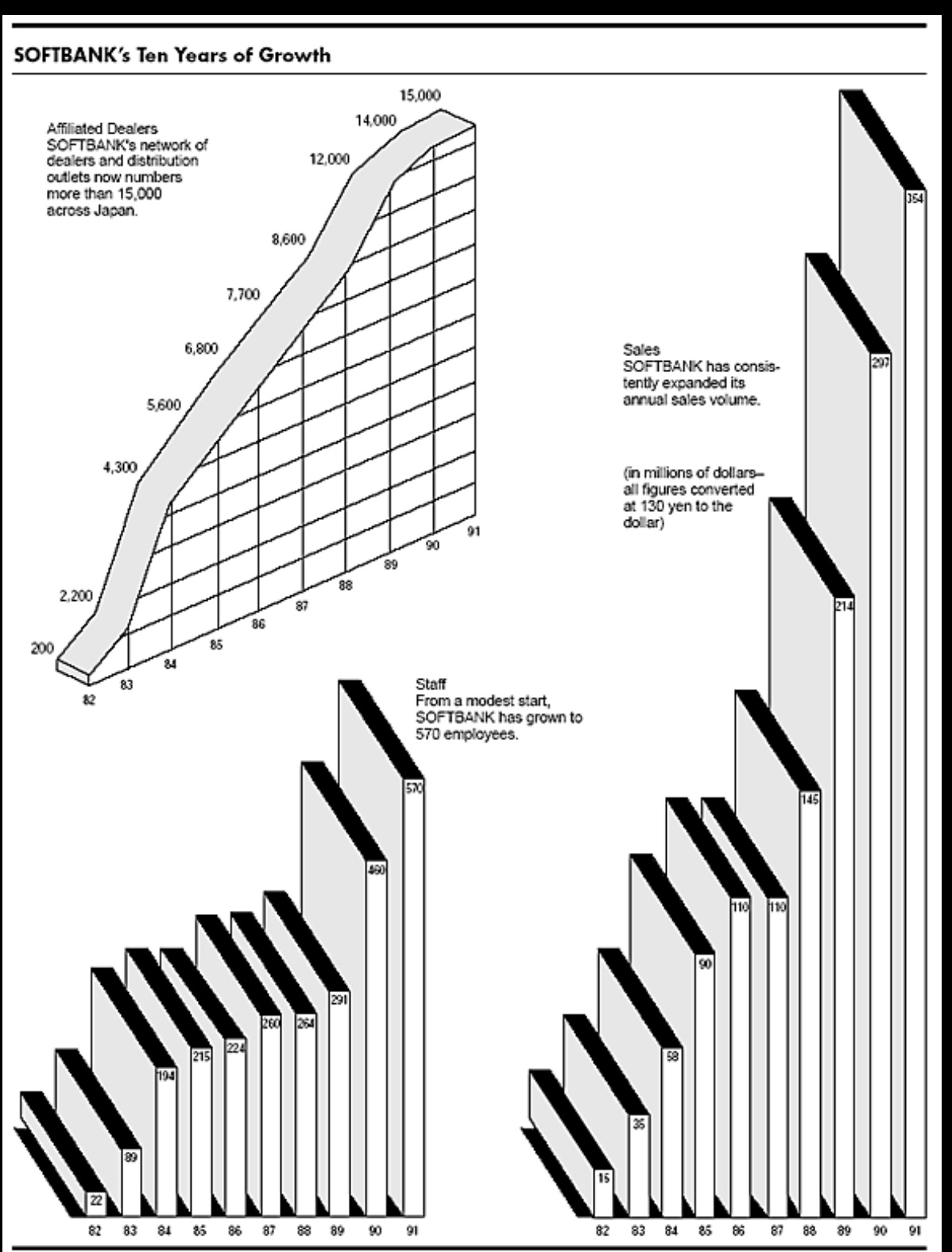

The first 15 years of SoftBank were devoted to the development of these two ideas (software and data). SoftBank first became a reseller of software (2 people initially, 570 in 1991) and then gradually became the main publisher of computer magazines. The growth is phenomenal:

SoftBank's DNA is in its early years: the choice of the sector of the future par excellence and the forced growth to become number 1. Masa Son is not an inventor but an amplifier.

After these two successes Masa Son launched into the Internet with more or less success: the investment in Alibaba was extraordinary and the founding of Yahoo Japan was also a success. Attempts to dominate mobile infrastructure have been mixed. SoftBank bought Vodafone Japan, Japan's third largest mobile operator, in 2006 for scrap ($15 billion) and modernized it (introducing the iPhone in 2008). Today the company is worth $69 billion. The acquisition of Sprint, the third largest mobile operator in the United States, was not as successful, as the market is largely dominated by Verizon and AT&T.

The Vision Fund's strategy

This brings us to the Vision fund which, with its impressive size of $100 billion, takes SoftBank to the next level. Does Masa Son exploit its aura and the orgy of liquidity swallowed up in unlisted securities to extract the maximum possible management fees (especially since a Vision fund of 2 up to $100 billion is planned)? Is he falling into megalomania? Is he taken by the typical undifferentiation of a bubble, being ready to invest in anything that moves as long as it is related to artificial intelligence? We would be tempted to answer yes to each of these questions, but our thesis is that there is a real strategy to explain these fundraising activities:

the main effect of the Internet (even more so the mobile Internet) is the removal of friction. It is becoming very easy with the Internet to carry out transactions. From this point on, the customer does not have to make any compromises and goes to the offer that exactly meets his needs. The choice becomes binary: this is precisely what he wants or he rejects it. The precise function (e. g. housing, moving) takes precedence over the object which is multifunctional: a car is used to transport goods, objects, social proof, etc.). The company that is able to respond most effectively to a function takes the lead and crushes all competitors: word of mouth (information flows without friction), scale effect and network effect combine. With the Internet, there is a clear winner in each category: Google for information, Amazon for shopping, AWS for the cloud, Facebook for social, etc. It is therefore necessary to aim for the number 1 position or stay on the frame. This dynamic is very well adapted to Masa Son who has never hidden his ambition to become number 1 in everything he touches. And that's rational.

Financial markets' appetite for technology has changed significantly since the 2000s: after the Nasdaq crash and long after, it became very difficult to raise funds. Technology companies had to grow by the wrist, i.e. through the cash flows they generated. Amazon has become number one in e-commerce through its operational cash flows that are constantly reinvested in growth. You had to be frugal then. Today, there is no shortage of sources of financing for technology companies. The trend has clearly been on the rise in recent years. The consequences of a very buoyant market is that a company can deploy its investments much faster, with negative cash flows. The Netflix case is instructive: until 2007, Netflix occupied a niche, DVD rental. The company's operating cash flows were very positive (24% of revenue in 2007). Then Netflix starts streaming (a typical internet business that eliminates friction). Reed Hastings, its CEO, knew that you have to be number one, which is no small feat compared to Disney, Fox, etc. He made the bet, investing in production on a forced march, not hesitating to take advantage of the "easy" financial context to put the company in negative cash flow and accelerate its expansion. In 2012, Netflix went into zero cash flow, in 2015, negative cash flows represented 11% of revenue and in 2018 17%! Netflix is now well ahead with more than 150 million subscribers and more film investment capacity than Disney or Comcast. In a different context, you have to adapt your strategy, it is all the genius of Reed Hastings who has taken all the major media companies by surprise. SoftBank also knows that today, there is a race to be number 1 and that traditional management by maintaining positive cash flows is risky.

SoftBank, in addition, is interested in what the Internet and Silicon Valley are particularly neglecting: the fusion between the digital world and the real world. This is phase 2 of the Internet, which seeks to use digital technology to move the physical world, thanks to artificial intelligence. The first phase was more focused on curation (sorting information) and it was rather appropriate in a context of tense financial markets (2000s) because curation is not very capital intensive: hence Facebook, Google, Salesforce, etc. But if the first phase, the easiest, has reached maturity, the second, much more important (ratio 20/80) is the future: this is what Masa Son sees. The problem remains that moving the physical world requires infrastructures that are very capital-intensive: Netflix is far out of date…

Infrastructures cement a competitive advantage obtained through a high-performance digital application. This is the example of Amazon: the quality of curation (the choice of products) required the construction of robotic fulfillment centers, the purchase of truck fleets, etc. Simplicity for the user requires great operational complexity. The merger between the two gives the maximum competitive advantage because replication is almost impossible. Similarly, Google's competitive advantage is cemented by its network of servers that cannot be replicated. In the 2000s, there was time to build these infrastructures with cash flows because competition could not easily access external sources of financing. This is no longer the case. Building a business that connects the digital world and the real world requires speed, the number one position is at this price. It's a billion-dollar battle and SoftBank understands it well. This explains the gigantic size of Vision funds 1 and 2. Silicon Valley often tends to neglect infrastructure (the dirty work), which is essential to maintaining a competitive advantage. Even Amazon cannot break through the Wal-Mart fortress with its 4,800 stores to break into the online food business. The Wal-Mart infrastructure is closer physically to the customer than Amazon's and is essential for food that has an increasingly local aspect.

SoftBank's added value since its creation is its know-how to produce strong growth. It does not invest like a venture capital fund in lottery tickets but in businesses that already have an advantage, to amplify their growth. Thus, the investment in Uber dates from 2018, the investment in WeWork from 2017 and 2019, the investment in Slack from 2017. The companies in question were already leaders but SoftBank wants to accelerate their growth. Let's take the example of Uber, whose potential could increase by a factor of 10 with the introduction of autonomous cars (significantly reducing the cost of the trip). To facilitate this future, SoftBank has invested $1 billion (with other manufacturers) in Uber's autonomous car division. Uber, like WeWork, are in negative cash flow to invest in growth, the Vision Fund and its mountain of cash can solve their problem. If Uber invests too little in autonomous cars, he risks being overtaken by General Motors (Cruise Automation), which could form an alliance with a competitor. SoftBank is therefore investing in Cruise Automation to control the threat (SoftBank has obtained a position on the board of directors). To better understand the added value that SoftBank can bring, this interview with Marc Andreessen by Elad Gil, author of the High growth handbook is useful. Today strong growth implies a lot of money to make good acquisitions and SoftBank is ideally placed with both Vision Funds.

Finally, contrary to appearances, Masa Son is more of a value investor. The investment in Vodafone Japan was made after Vodafone's failure in that country at a very low price. Sprint was also bought cheap but remained cheap (probably a value trap). The investment in Uber followed the same pattern: Masa Son came after the exit of the sulphurous founder Travis Kalanick, who by his excesses re-inflated Lyft. SoftBank was then able to invest at a significant discount from previous valuations. Masa Son sees a driverless future for Uber where the number one position will give a huge scale advantage. The case of WeWork is also interesting. We have been very disappointed with SoftBank's $2 billion investment on a $47 billion valuation. If the IPO is made at $14.5 billion, SoftBank will have lost $1.4 billion on this portion. According to CNBC:

Investors like SoftBank benefit from an obscure protection that will grant them hundreds of millions of shares if the value of WeWork's IPO is lower than the one they bought on the private market.

The small print, known as a ratchet, reflects the opaque nature of private markets and very high valuations. The parent company of the real estate start-up was valued at $47 billion after its last round of financing by SoftBank.

by this clause, SoftBank could recover $400 million in discounted WeWork shares. Masa Son, as a good disciple of Benjamin Graham, structures deals with preferred shares and warrants to protect his back. This is all the more necessary in the financing of very complex operations such as infrastructure.

To understand SoftBank, it is better to look at China and Alibaba than Silicon Valley. The Chinese are very pragmatic and do not hesitate to put their hands in the sludge and deal with material things. Silicon Valley is more ethereal and willing to stay in the digital world. Alibaba has made the transition from the purely digital platform of the early years (very Silicon Valley) to "new retail", which consists in integrating digital throughout the economy to modernise it. The consequences are significant:

a decrease in the immediate return on investment due to the infrastructures to be developed: from a low marginal cost (Okta, MongoDB, Zoom, Datadog) to a high marginal cost (Uber, WeWork, etc.)

a deeper, and more difficult to attack, competitive advantage, as the margin of profitability for number 2 is non-existent.

This is the path followed by SoftBank, which chose to attack the 80%, leaving the 20% to Silicon Valley. It’s a difficult path with high reward and high risk: infrastructures are costly.