cemeteries are full of companies that didn’t understand the power game.

I made a mistake last week by attributing to Marc Andreessen remarks about the commercial's fighting spirit. These remarks were in fact made by Mark Cranney, another associate of Andreessen Horowitz.

Here is really ch’i:

From Retail Brew (November 13, 2019):

Amazon’s on the cusp of its biggest grocery investment since its $13.2 billion Whole Foods acquisition in 2017. The vibe: an affordable, no-frills supermarket like the five already in your neighborhood.

CNET reports that Amazon is opening an Amazon-branded grocery store in LA’s Woodland Hills neighborhood next year. Amazon didn’t provide a name for the new chain but confirmed it will have traditional checkout counters and will not have vegan, sugar-free kombucha.

A new chain could bring Amazon closer to fulfilling its grocery ambitions, such as…

Increasing customer loyalty. Almost all grocery shopping in the U.S. still occurs in stores, so an Amazon chain could meet customers where they are better than expanded delivery services.

Making inroads on its nemesis. Walmart is still the largest grocery seller in the U.S. and offers online and brick-and-mortar purchase pathways.

Looking ahead...Amazon is reportedly exploring more grocery store openings in San Francisco, Seattle, Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia, per the WSJ.

This latest investment from Amazon is particularly surprising at first glance. It is not innovative. On the contrary, it seems to be a return to the past, the time of grocery stores around the corner. To understand, we must go back to what is the specificity of Amazon and its problem with groceries.

Wal Mart: the master watchmaker

The consumer when he decides to go shopping must make a trade off between: 1 / the possibility of choosing the product, 2 / its price, 3 / its accessibility. For the distributor, it is an optimization problem between the three variables. Wal Mart was for a long time the master of this optimization, the great watchmaker. Its method? The control of the land. Cleverly, the company had chosen to conquer middle-sized cities, starting with Arkansas, settling in their periphery. This strategy had several advantages:

the absence of serious competitors, the latter being more interested in high density areas,

the low price of the installation,

the possibility of building large areas with large car parks,

easy access by car,

but two serious disadvantages:

the modest standard of living of these cities,

their low density.

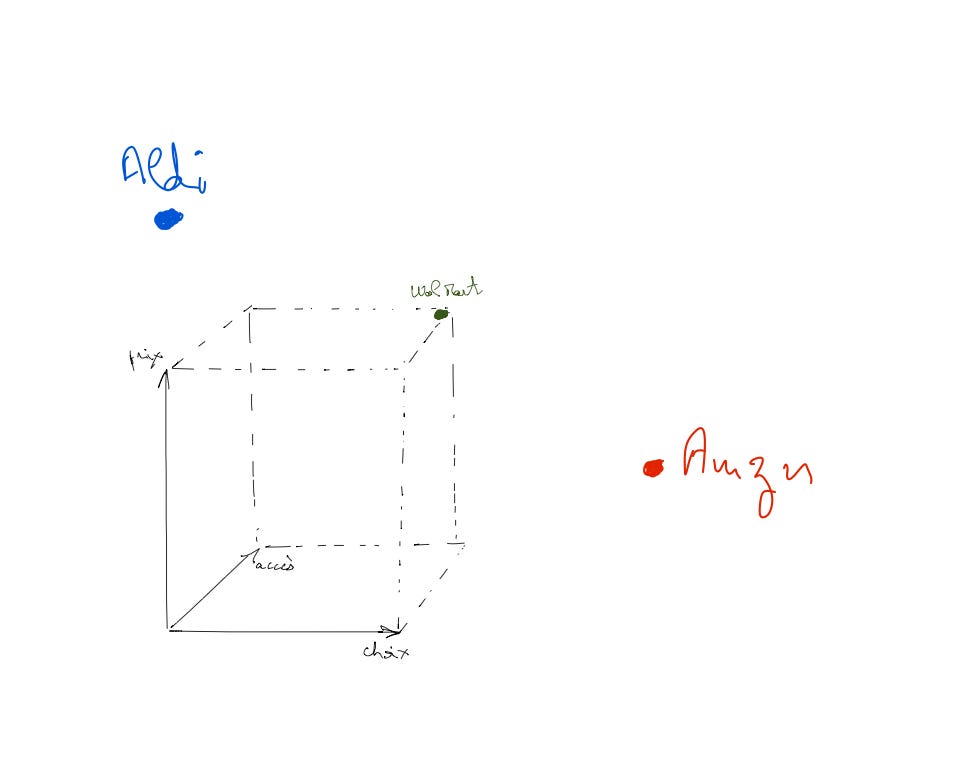

These drawbacks forced Wal Mart to adopt an extremely efficient organization, a precision mechanism, to offer a wide choice at a low price, in constant rotation. The mastery of information was key to know the needs of customers, find the corresponding products, bring them from far to have the best prices and rotate them to the maximum to offer cheap prices. It can be said that the success of Wal Mart has been based on the implementation of an unparalleled information system that has allowed the optimization of a limited physical space to offer choice, price and access. Wal Mart systematically exceeded its peers in terms of sales per m2, which provided the fuel to expand year after year throughout the United States and internationally. Today Wal Mart has more than 11,200 stores in 27 countries. A typical hypermarket is 10,000 m2 but the superstores are more like 16,000 m2! Optimal use of the land is crucial. The following chart shows the optimal positioning of Wal Mart on the three variables as well as that of Amazon and Aldi:

Amazon has blown up this subtle balance, based on land’s mastery, creating globalized abundance online: the choice has become the key variable; the other two were an afterthought in the short term. This is Clayton Christensen revisited: break an existing integration by proposing a very superior product/service at one point of the chain and then build a new integration around that point. The theory is here. Jeff Bezos has changed the game by no longer trying to solve a space optimization problem, but to provide abundance above all, with stock turnover being secondary. While a superstore offers 140,000 products, Amazon offers 500 million. The two companies have a lot in common, especially their frugality but it is especially the emphasis on the computer that brings them closer together. For Wal Mart, it serves to optimize the use of the land, for Amazon it allows to know the customer to guide him in his Alibaba cave. Amazon has built its infrastructure around this goal and it can not be more different from that of Wal Mart: 175 treatment centers for a total area of 14 million m2, or 80 000 m2 per center. These centers therefore have a very high radius of action. To give an idea, if we consider the total surface area of the earth, a Wal Mart super center covers a radius of 65 km while an Amazon processing center a radius of 500 km. By giving priority to choice, Amazon has sacrificed the speed of access (it is necessary to organize a long-distance transport) and the price (the establishment of the marketplace has multiplied by more than 2 the number of products offered but the merchants have no constraints on the prices they display). Having a huge superiority over the range of products offered for sale, it is only up to Amazon to improve gradually on the other two variables to win the cake: the retail market estimated at $ 25 T, or more than the GDP of the United States ... And that's what it does: after delivery in 2 days, it is now delivery in 1 day. From The Verge (October 24, 2019):

“We are ramping up to make our 25th holiday season the best ever for Prime customers — with millions of products available for free one-day delivery,” said Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos in a statement. “Customers love the transition of Prime from two days to one day — they’ve already ordered billions of items with free one-day delivery this year. It’s a big investment, and it’s the right long-term decision for customers. And although it’s counterintuitive, the fastest delivery speeds generate the least carbon emissions because these products ship from fulfillment centers very close to the customer — it simply becomes impractical to use air or long ground routes. Huge thanks to all the teams helping deliver for customers this holiday.”

The company announced earlier this year that it would start testing a shift from Prime two-day shipping to one-day shipping. That’s on top of its existing services like Prime Now, which offers same-day shipping of certain products in certain markets, and Whole Foods grocery delivery, among many others spanning food and household item delivery. The company has also been aggressively building out its contract delivery service, Amazon Flex, and even started exploring robotic ground delivery. Drones for package delivery by air are also still in the works.

Amazon can also damp prices by offering Amazon basics that invade category after category (158 000 items today). The company has a wealth of information unparalleled on the products that sell best and can thus choose the best categories.

Amazon, however, has a big thorn in the foot: food distribution.

Amazon’s Achilles Heel

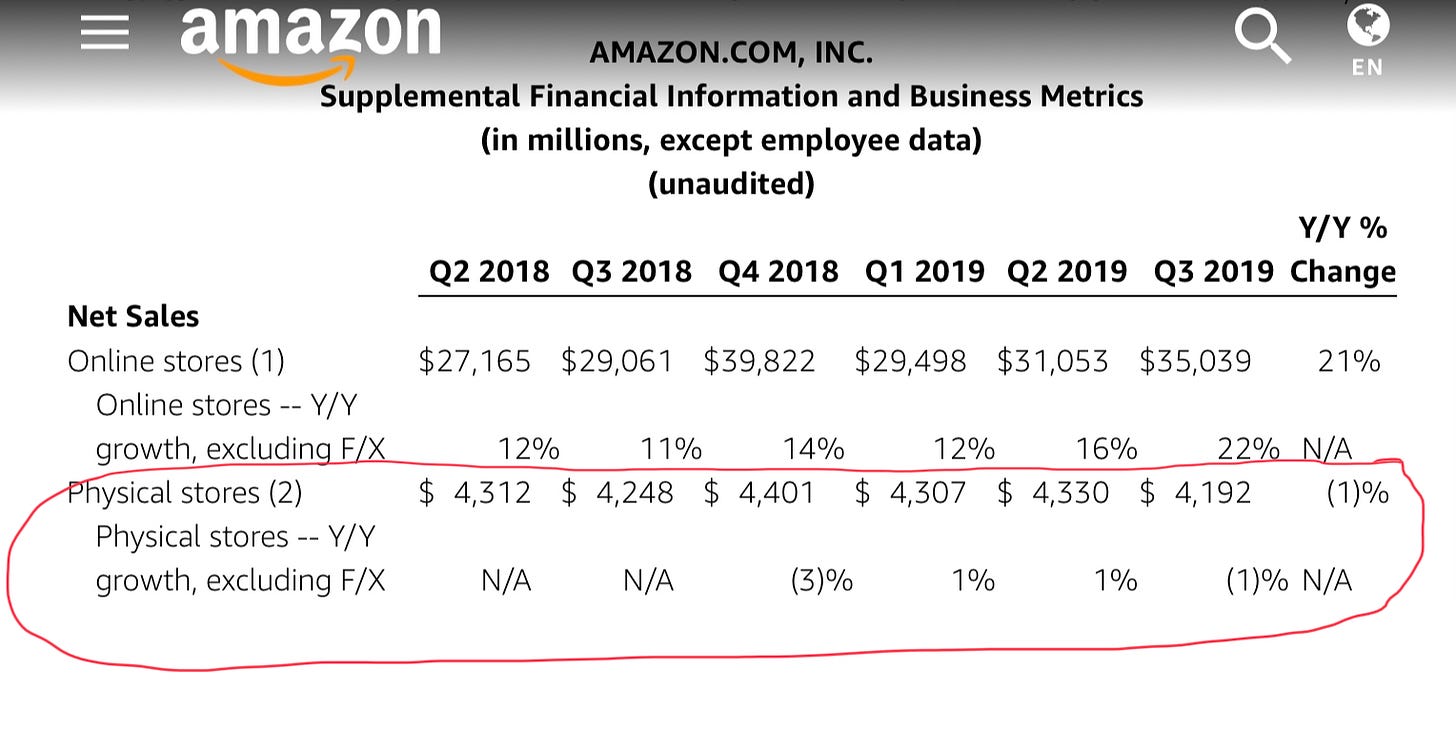

According to Google's algorithms, around 130 million books have been published worldwide. This explains why Amazon started with book delivery: easily transportable abundance. What variety of food do we need daily? We are talking about 20 to 30 different types of foods. Food distribution has adapted to our morphology: we do not need a huge choice. This is not really the kind of context where Amazon is comfortable. To top it all, food products perish quickly, can not languish in a fulfillment center and are difficult to transport. Wal-Mart's infrastructure with its many convenience stores, its optimization culture, inventory rotation, is much more suited to food distribution than Amazon's. Witness the recent results of Wal Mart. From the Wall Street Journal (November 14, 2019):

Walmart said its US-based comparable sales of stores and websites that had been in business for at least 12 months had increased 3.2% over the period ending Oct. 25, marking a series of quarterly gains in terms of sales. Its online sales in the United States grew by 41% over the previous year, thanks to grocery orders ... Walmart has developed the grocery delivery online because it competes with Amazon.com Inc. as the most convenient purchase option for Americans. In the United States, it now has more than 3,000 points of sale where customers can go by car to go shopping and more than 1,400 points of sale at home.

Walmart is the country's largest grocer, with sales accounting for 56% of its total revenue in the United States.

"Our strength is in food, which is a good thing, but we still have some progress to make on Walmart.com for general merchandise," said McMillon. "We are better integrating these two business activities to get better margins, but there is still a lot to be done."

Wal Mart can attack online food sales through its convenience store infrastructure, which is typically smaller than super centers (4,000 m2). Online sales are up 37% in the 3rd quarter thanks to food. If abundance is no longer a criterion of choice, Wal Mart can fight on price and access, its natural strengths. This is the answer of the shepherd to the shepherdess: the company seeks to break the advantage of Amazon by a much higher service on food delivery, the goal being to use it as a basis to extend its advantage online to all e-commerce! It's easier to make a food delivery from a convenience store than from a 500-km fulfillment center. Despite its small margins, food distribution is a big challenge for both Wal Mart who wants to start its "remontada" and for Amazon who wants to avoid it.

Amazon's answer

True to its nature, Amazon fumbles, experimenting before finding the big shot. The first try was the acquisition of Whole Foods and its 500 stores in 2017. This allows it to bridge the gap between Wal-Mart's 3,000 convenience stores and, in particular, to acquire food logistics infrastructure. already depreciated, which will serve as a basis for future developments. Whole Foods has an organic positioning that differentiates it from Wal Mart (it's better when you're smaller). The problem is that organic crops represent less than 1% of the cultivated area in the United States and that land conversions are very slow to achieve. Whole Foods is therefore limited in its expansion. Amazon launched another concept in 2016: Amazon Go, the cashless store. In 2018, the ambitious plan was to open 3,000 stores by 2021. In the last release on Amazon's results in the third quarter, we no longer talk about Amazon Go. Only 15 supermarkets are available to the public. The concept of Amazon Go is interesting: knowing that the choice of food assortment is not the main issue, if the essentials are there, it focuses on one of the two other variables: access where it becomes unbeatable. It's easy and quick to get in and out of the store without having to take out your wallet. Amazon Go's strategy is bold but it has two disadvantages:

It does not allow Amazon to build an infrastructure for home delivery. There is very little staff in each store and the AI is function-oriented: take and carry. So the potential leverage is limited.

It sacrifices the price variable. The cost of hardware for Seattle's first store was estimated at $ 1 million, or $ 6,000 per square meter. Even if we can estimate a decrease of this cost in the coming years, it is prohibitive to practice low prices. The cost of interior design for a traditional grocery store is $ 1,000 per m2 and for a hard discounter of $ 300 per m2.

We can not say that growth is just around the corner for Amazon's stores! While Amazon gropes and Wal Mart invests in home delivery, a third actor hounds the two groups, pounding their margins, taking market share and making their food distribution strategy tricky: the hard discounters.

The breakthrough of hard discount

There are now 4 hard discounters in the United States: Aldi, Lidl, Trader Joe's and Save-a-lot to which we can add 2 brand discounters: Dollar Tree and Dollar General. Apart from Lidl who missed its entry in 2017, with notably too large stores, the others behave in Genghis Kahn of food distribution as shown in the following table taken from the excellent Retail disruptors :

The economic model of hard discounters is as simple as it is daunting:

they focus on essential foods, those that are bought every day and quickly, those for which the choice is rather a disadvantage. Their assortment ranges from 1,000 to 2,500 products in shops of 100 m2 close to the people. A supermarket offers 25,000 to 40,000 products (a real headache when you're in a hurry).

As it is very easy to buy in a small store near home with a small assortment, and the customer knows pretty much what he wants, sales by product are far superior to other forms of distribution: the scale is 10 to 1.

Discounters offer unbeatable prices because they use private labels with which they can sign very advantageous long-term contracts. These labels are guaranteed strong sales that they can not achieve anywhere else.

The low margins allowed by discounters are more than offset by the volume of sales by product. The overhead and real estate costs of hard discounters are minimal. The set is a successful cocktail for profitability.

As a result, hard discounters can reinvest their profits in expansion and gain market share on Wal Mart and others.

Discounters have annihilated the choice parameter that benefits Amazon (and Wal Mart on a lease extent). They maximizes the other two parameters (price and access). They are therefore better positioned than Amazon and Wal Mart on their niche.

The grocery store is a springboard

The superiority of hard discount in food distribution is not unlike that of Netflix in the media. In both cases:

we are dealing with pure players who dominate their industry by a simple recipe: in the case of Netflix, it is the abundance of films coupled with a superior user interface, in the case of hard discount, it is the ability to offer ultra-low prices on essential items,

these pure players are surrounded by giants who are interested in this industry for reasons that are external to it.

This is how many Netflix competitors emerged: Disney + which uses streaming to introduce its subscribers throughout its universe: Disney-parks, etc. Prime Video which is used to sell premium subscriptions monetized throughout the Amazon universe, Apple TV + which is used to sell iPhones, etc. These players do not necessarily want to make money with these offers, they use them as appeal products. To break through, they adopt different strategies than Netflix, they do not fight on the same variables. Disney uses its characters, Apple will make photo shoot movies, Prime Video innovates.

Food distribution is also a springboard, so both Amazon and Wal Mart will continue to devote significant budgets, but with a different strategy than hard discounters; better not to be slaughtered on the opponent's court. To monetize Prime Video (and limit the investments on its own very expensive productions), the company packages subscriptions to Starz, HBO, DISCOVERY, etc. These subscriptions are pure margin for Amazon and allow the company not to be slaughtered by Netflix. Similarly, in the grocery store, to monetize its online offering, Amazon mixes it with a groceries marketplace. This is also pure margin and the delivered food may be riper than those that Amazon delivers over long distance.

Artificial intelligence changes the game

Artificial intelligence is a prediction tool. This tool became operational when the CPU chips were traded for GPUs for training neural networks in the 2010s. Since then, the computing power and the amount of data helping, the forecasts are constantly improving at an increasingly affordable cost. Forecasting is the basis of all our actions, so we must expect to see the AI land everywhere and be able to analyze the consequences.

A distributor is primarily a seller, a merchant. It seeks to meet the customer's need, to predict what they will buy to present it to him. Amazon uses algorithms to give customers ideas based on things they look at, their purchase history, and so on. The forecast is still imperfect but it is improving. Assume that this forecast is reliable at 5% for a given product. This means that for 20 customers in the same neighborhood who might buy the product as detected by the algorithm, Amazon is sure to sell at least one. He can therefore bring the product closer to the customer even before the latter triggers the act of purchase. But the 5% reliability will become 10%, 30%, 60%, etc. Thanks to AI, the challenge now is to bring stock to potential customers: bringing a product from a warehouse 500 km away will become archaic. The pressures linked to global warming will reinforce this archaism. The product will be available on the spot, either by short distance delivery, or in a convenience store. It will be a giant step for Amazon who can commit to delivery in two hours for all products, or even better! Amazon plans to recreate an optimization between abundance and access to a level beyond the reach of Wal Mart, thanks to AI. Its advances in the cloud give him a big head start.

Why Amazon launches a traditional grocery store network

Amazon needs a local infrastructure to carry out its blitz project. And quickly because Wal Mart, and this is its specialty, knows how to optimize local inventory management and could rely on a third-party AI to create abundance upstream from its own fulfillment centers (more than 30 today).

Amazon must therefore create many convenience stores and the logistics that goes with it to quickly compete with the more than 3,000 displayed by Wal Mart. Food is the obvious starting point because it is the daily expense of households, so the opportunity to create goodwill with impeccable service (it remains to be defined). The grocery store will be an advertising vehicle for all of Amazon's services (fast return on investment), the Amazon brand is therefore essential. But, beyond, convenience stores will be a way to implement Amazon's AI, bringing food and other stocks closer to potential customers through powerful prediction algorithms. These stores will be designed to allow home delivery (and probably returns as we will see a little further). This explains why Amazon Go is not suitable. They will have to grow like mushrooms, which explains that the Whole Foods format is not suitable (not enough organic food on the market). In short, the ideal format is the good old traditional grocery store under the Amazon brand.

Go local seems to be how the future goes, whether through AI progress or because of climatic constraints. Wal Mart is left with an infrastructure edge, Amazon with an AI edge, AWS being the undisputed leader in the cloud. Which company will win? Should these companies capitalize on their strengths or fill their weaknesses?

For Wal Mart the answer seems obvious: further strengthen its local infrastructure and outsource the AI to Microsoft or Google. Wal Mart has no chance on AI. However, Wal Mart will miss Amazon's deep knowledge of its customers.

For the latter, closing the gap on local infrastructure is a priority. There is no point in getting ahead in AI if you can not implement the predictions.

Beyond that, it is to be expected that Amazon pushes its AI advantage until it changes its business model: delivery before the purchase will supplant the purchase before delivery. If the prediction is 98% effective, this new model will capture the customer at a lower cost than the current model. It will be then difficult for Wal Mart to find the parade